I have lost count of the number of times we have planned

our trip to Russia. Every year, sometimes literally days

before we are due to leave, there has always been an email

or a phone call from our contacts cancelling for one reason or

another. Either the weather had changed, or the mine owner

had gone AWOL, or our filming permits had been declined

even though days before they'd been approved.

Even the week before I was due to leave, I

got a call at 4am whilst I was in America,

and was told that Pallav, our ‘fixer’ (the

person tasked with organising the trip

once we got there) had the wrong dates on

his visa. Deciding to try and arrange our

journey to the mine ourselves, we repeatedly

tried to get hold of the mine owner, Dmitry,

to ask him to meet us off the plane. But that

seemed to be easier said than done, because

we couldn’t get hold of him. The next day as

I was boarding the flight back to the UK, I

was told the trip was cancelled.

The second we touched the tarmac at

Heathrow, I switched on my phone and

received an urgent message from my

assistant Barry to call him immediately.

Barry, through another friend of mine

Eugene, had managed to track down Dmitry

who apparently had taken a few days off

with his children. However, when Pallav

realised that he couldn't make the trip, he

had cancelled all of our internal flights! So

Barry had rebooked them and agreed with

Dmitry that we would still visit. We were to

meet up with Eugene who would also fly to

Neryungri (the nearest small airport to the

mine) and act as a translator for us. The only

problem was Barry had rebooked the flight

for the following day and that was my son

Louie’s first birthday and there was no way

I was going to miss that. So we decided that

Alex, my cameraman, would travel out as

scheduled and I would take a later flight that

evening to Moscow.

My wife questioned my sanity; “Why would

you want to visit a mine, half way around

the world, which is almost depleted?” But for

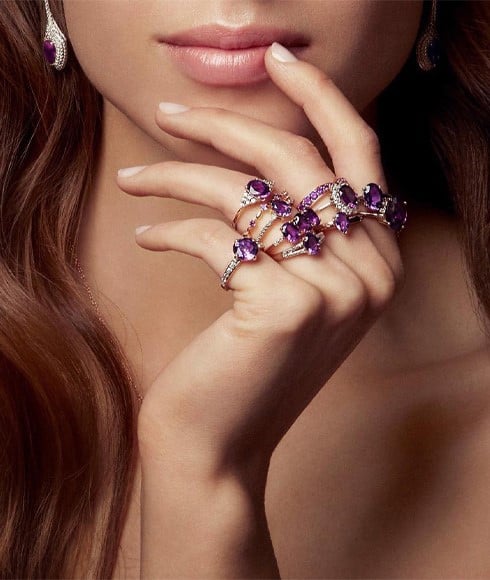

me that’s the point. Chrome Diopside (also

known as Russian Diopside) has always been

one of my favourite gemstones and nobody

I knew in the gem world had ever been and

seen the mine. I wanted to see it, feel it,

touch it, understand it and as always take

videos and photos to share with others who

share the same passion.

Everything I had ever learnt about the

Chrome Diopside mine was passed on

second-hand through the gem trade and I

hate being in that position. With most other

mines that I haven’t yet visited, at least

normally I am secure in the knowledge that

it is one of my closest friends or colleagues

who has been there and therefore I know

my information is reliable. But with Chrome

Diopside, everything I knew was from talking to people in

the trade and from research articles on the internet. So you

see, I just had to go and find out for myself.

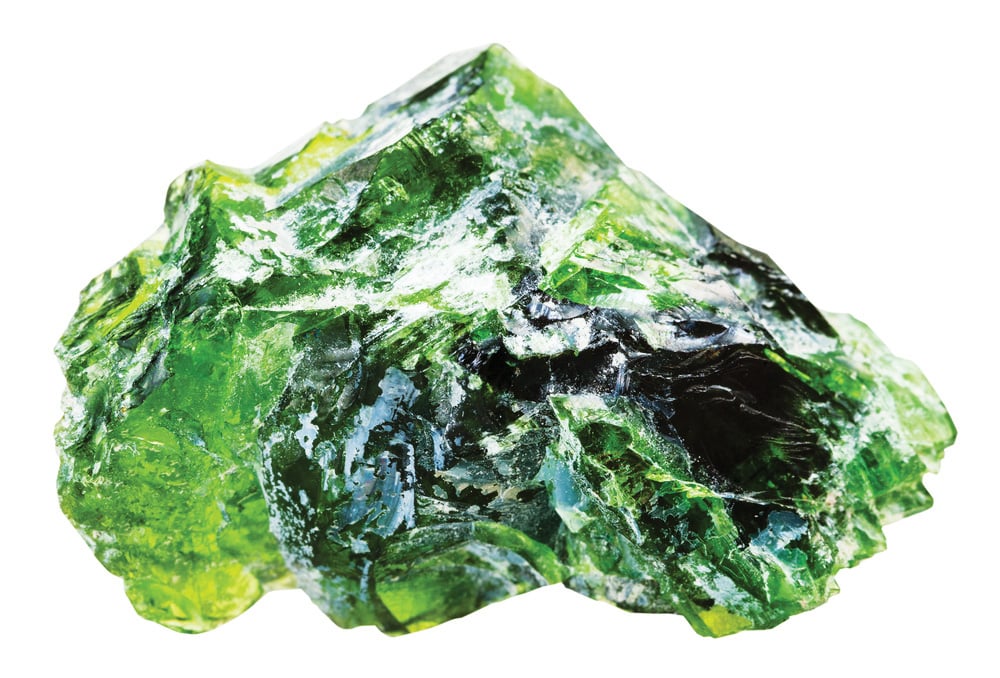

Considering its hostile growing conditions were in

metamorphic and igneous rocks, it’s amazing that with

such a difficult home life Chrome Diopside often arrives at

the surface of the earth un-scarred! No wonder locally they

refer to it as the Siberian Emerald or the Million Dollar

Emerald. When you discover a piece that is clean, and

I mean really clean, with its vivid green saturation, that

bathes in sparkle due to its high refractivity and when you

remember where it grew up, you might pause and wonder

whether this is one of the finest miracles of nature you

have witnessed.

Talking of its brilliance, Chrome Diopside has a higher

refractive index (R.I.) than its two nearest green rivals.

Emerald has an R.I. of 1.56 to 1.6 and Diopside’s nearest

competitor, Chrome Tourmaline has an R.I. of 1.61-

1.66. With Chrome Diopside taking podium with an R.I.

of 1.663–1.699, it’s easy to understand why when cut

properly, the gem is a real head turner. Its name is derived

from the Greek word dis, "twice", and òpsè, "face". This

two faced gemstone has perfect cleavage in two directions

and its name is in reference to the two ways of orienting

the vertical prism.

But why are we travelling to the far off lands of Siberia,

just outside of the Arctic Circle, some six time zones

away even from Moscow, when after all, it is reported that

Chrome Diopside has also been found in Afghanistan,

Austria, Burma, Finland, India, Italy, Madagascar, Pakistan

and Tanzania? Well to-date, I have yet to see a piece of

Chrome Diopside from any of those countries that is worth

faceting. It’s encouraging that the mineral has been found

in these areas, and where there are traces, there is hope

that gem grade will be discovered, but to my knowledge

none have been uncovered yet.

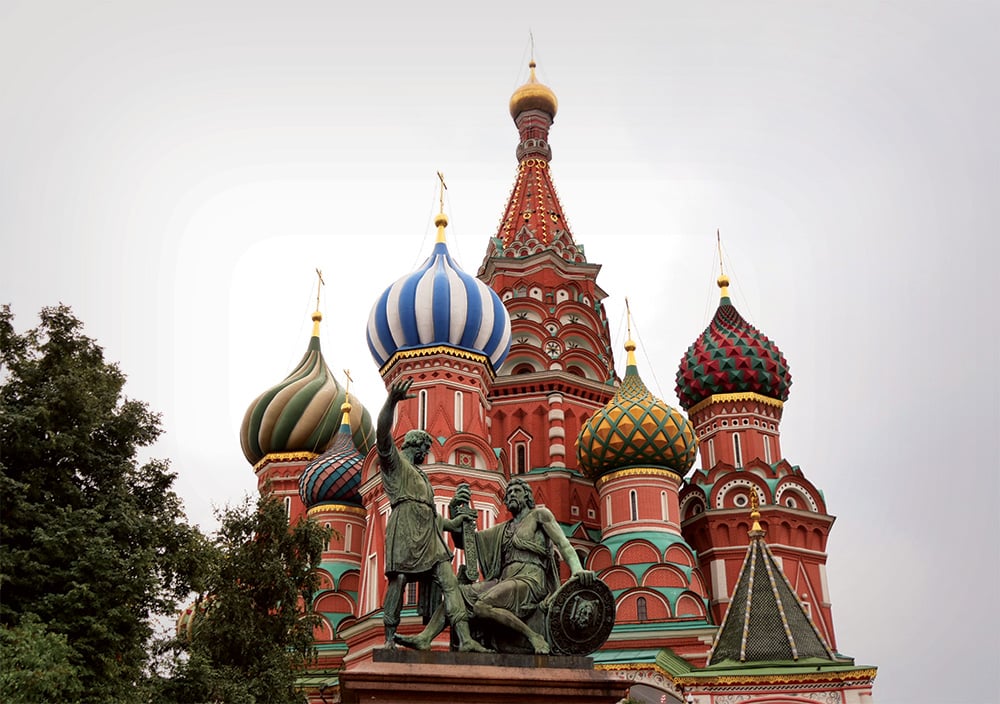

I arrived in Moscow at 4am and got a taxi from the

airport to the centre of the city. I arrived at the hotel to

find there was no room reserved for me, (or at least that’s

what I thought the night porter was telling me!) After

travelling through the night I desperately needed some

sleep, so I asked for the room number of my cameraman

Alex and woke him up and slept on a tiny little sofa in his

room. After a few hours’ sleep, we went out and explored

Moscow. I had always wanted to visit the city and we had

a great time taking in the sights. We visited St Basil's, The

Kremlin, Red Square and the Aleksandrovsky Gardens. At

around 5pm we headed off to the airport.

The flight to Neryungri was itself quite an event. It took

off at 9pm and with neither of us speaking a word of

Russian, all we could make out was that it landed around

9.30am the next morning. At about 1am I lifted my

window blind and looked out of the window and to my

amusement painted on the wing of the plane was a logo

that looked very reminiscent of our old Gemporia logo!

But what surprised me even more was that it was already

broad daylight. I was really confused. It seemed crazy that

it was 1am and brightly sunlit. But as we were travelling

east, for every hour in the air, we were advancing one time

zone earlier! The flight only took six and a half hours, but

according to the clock, we landed twelve

hours later.

It seemed crazy that

it was 1am and brightly sunlit. But as we were travelling

east, for every hour in the air, we were advancing one time

zone earlier!

We landed at the airport which looked like it had

been built in the forties and hadn’t had a single bit of

restoration work carried out ever since. It was like stepping

back in time. For the documentary we were making, Alex

tried to film me walking down the steps of the plane

and immediately, out of nowhere came a huge Russian

gentleman in uniform who gestured in no uncertain terms

that Alex was breaking the rules.

Right on schedule, Eugene arrived to greet us and we were

all ushered like sheep into a tin shed where the baggage

handlers literally threw and kicked the delicate camera

equipment in our luggage! Eugene excitedly showed me

a photo of the airport back in April when his previous

attempt to reach the mine had failed due to the weather.

In the car, Eugene, who has been a geologist for over

forty years and who has mapped out many areas in the

region, (including Mirny where the world’s second largest

Diamond mine once operated), began to provide us

with a wealth of information about the area. I had first

met Eugene in Tucson and ever since, he has been the

most reliable source of information about the goings on

in the Russian gem scene. The country is still not very

forthcoming with information, especially when it relates

to its precious metals and gem mining activities, much

of which is still under government control. The man is

a wealth of knowledge and even though the road was

extremely bumpy and at times a dirt track, he went into so

much detail about the area that the five hour journey to

Aldan passed quickly. Even though we were visiting in mid

August, as we drove we still passed through areas where

you could see snow on the ground.

Eugene explained how the Inaglinsky Chrome Diopside

deposit and vermiculite was located in the area of Central

Aldan’s gold-bearing region, Sakha (Yakutia) and was some

30km to the west of the town of Aldan. We would first go

to Aldan and meet up with Dmitry and together we would

travel to his mine. Eugene explained how the Yakutia

region was one of the richest areas of natural resources in

Siberia. There were deposits of Diamond (Mirny, Aihal),

gold and platinum (Aldan), Charoite south of Yakutia near

the Chara river, coal in Neryungri, and as we drove we saw

workers laying a huge pipe that is to eventually transport

gas some 5,000 kilometres from Northern Siberia all the

way to China.

The Central Aldan region is known for its gold and

platinum resources, where there are about 200 working

deposits and more than 400 deposits in the planning stages.

Eugene believed that there were more than 10 tonnes of

gold mined every year in the region and literally less than

one hundred metres from the Chrome Diopside deposit,

thousands of miners used to extract platinum.

Eugene explained that it was while carrying out geological

mapping in 1968 that geologist Anatoly Korchagin

made the discovery of Chrome Diopside in the valley

near the Inagli River. He had named this deposit Inagli

and continued for many years to explore the mineral’s

composition and geologic structure. In 1972, Dmitry’s

grandfather began mining the gem and his family have,

although sometimes sporadically, continued mining ever

since. Today, Dmitry owns the only legal permit for

Chrome Diopside in the area and the full extraction process

is under his careful control.

Dmitry’s

grandfather began mining the gem and his family have,

although sometimes sporadically, continued mining ever

since.

Eugene went on to tell me all about Chrome Diopside’s

host rock. Gem quality Chrome Diopside is discovered

in the metasomatic rocks (those which have been altered

chemically by the movement of water), not in the actual

pegmatites. The length of the chrome bearing vein is

approximately 800 metres long and its thickness varies from

0.5m to 3m. The key challenge is that it is running at 45

degrees into the earth. The size of the gem quality Chrome

Diopside crystals range from 3-4 mm to a maximum size

of 20 mm. The mining season is only 3-5 months because

during winter the temperature reaches -45 to -50°C.

The mining season is only 3-5 months because

during winter the temperature reaches -45 to -50°C.

I loved listening to Eugene as we drove. At 64 years of

age, he is so passionate about geology that I probably

learnt more during the journey than I have in the past few

years. Throughout the entire drive we were surrounded by

thick forests of what seemed to be a variety of Pine and

the occasional Silver Birch. After five hours of extremely

bumpy roads, we arrived at the small, rustic and remote

mining town of Aldan.

Here, we met Dmitry and jumped into his

4x4 and set off on an even bumpier dirt

track for a further two hour bone-shaking

ride. As we drove, Eugene explained to

Dmitry that we not only wanted to visit

the mine, but also take photos and videos.

Without understanding a single word

of Russian, I could tell the conversation

wasn’t going well. Alex and I looked at

one another and both realised that Dmitry

didn’t want his mine filmed!

We had travelled half way around the world

to film the mine on behalf of our following

of gemstone evangelists, who just like us,

have a thirst for knowledge and a better

understanding of where gems are unearthed

and it appeared that Dmitry wasn’t going

to let us get our cameras out of their bags.

With Dmitry driving and Eugene in the

passenger seat, from the back of the car I

leant forward inbetween them and insisted

that Eugene translated my request. After

what must have been forty minutes, Dmitry

seemed to grasp the purpose of our filming

and eventually started to nod his head in an

approving kind of action.

I think it’s important never to forget that

gemstone mining is normally a secretive

affair. Mine owners are not keen to publicise

their location, as one of the biggest issues

with mining precious gemstones is theft.

In remote locations, it’s almost impossible

to prevent illegal miners coming onto your

land, especially in the evenings and during

closed seasons. One of the biggest costs for

most of the mines I have visited over the

years is security. But I explained to Dmitry

that being able to show the world where

the gem comes from, in this modern age

where we all passionately care about origin

and ethics, in an era where our quest for

knowledge has never been greater, telling the

story and showing the source is crucial.

We approached the mine, then continued

straight past it! As I began to wonder

whether we were still facing a breakdown in

communications and whether our cameras

would ever see daylight, Eugene explained to

me that Dmitry first wanted to drive us to the

top of the Inagli Valley. To fully appreciate

the geology of the location here, we would

get a bird’s eye view of the landscape. As we

looked down the valley, Eugene explained

how in 2004 there were over two thousand

miners extracting platinum from the floor of

the valley. He then pointed to the left of the

valley and in the distance we could see the

Diopside mine.

I asked Eugene why we couldn’t see the

Mirny mine from this high vantage point.

From my previous research I had assumed

for many years that Chrome Diopside and

the Mirny Diamond deposit sat on the same

kimberlite volcanic pipe. He explained that

there were many volcanic pipes in the area,

but Mirny was a little way north of this

deposit and I had been misinformed that it

was the discovery of this Chrome Diopside

outlet that had resulted in the discovery of

Diamonds at Mirny.

Let me provide a little bit of a background to

this misunderstanding. It is well documented

that geologists use the presence of Diopside

as an indicator for Diamonds. If they

can successfully piece together the mass

movement of rocks from millions of years

of glaciers, tectonic plate movement, several

ice ages and a myriad of other earth moving

events, then they can identify where the

Diopside originated – up-slope, up-stream,

or up-ice from the location in which they

were found. A trail of Diopside fragments

can lead a Geologist to the pipe from which

they were weathered. This activity, known

as "trail-to-lode" prospecting is how many

Diamond deposits are discovered. Hence

the internet is full (I hope this will all get

amended after I publish this article) of

accounts of the Chrome Diopside and the

Mirny mine being situated on the same

volcanic pipe. As we descended back down

the valley, a huge downpour greeted us.

Eugene explained that in just a few weeks

from now, the rain would be replaced by

snow. We arrived at the mining site and

Dmitry’s security guards lifted the security

barrier and with a military-style gesture we

were welcomed into the compound. Now on

foot, we rounded the corner to the previous

working face of the mine and my eyes almost

popped out of my head as we were faced

with a solid green wall of Chrome Diopside,

back-dropped by a magical rainbow that had

formed as a result of the storm we had just

driven through.

As I faced the huge green wall of

sparkling Chrome Diopside, with its

otherworldly glow, my mind began to race.

Had the rumours of depletion been a

marketing ploy? Was Chrome Diopside not

as rare as everyone had been saying?

We got closer and it quickly became apparent that the wall

was really made of chromium dust, chromium agglomerates

and only the very occasional small piece of transparent

facetable grade material.

As we studied the vein, Eugene told us that he believes that

the gem originated from within the mantle and not the crust.

Based on all the photos I had studied, I explained that I had

always thought that the gem had been formed at the base

of the crust and arrived at the surface in xenoliths. Eugene

went to great lengths to explain the local geology to me, even

drawing me a diagram. Now, as I was standing here in the

only gem deposit of its type, I had to agree with Eugene that

this gem probably did originate in the mantle. This further

reiterated why it’s so important to visit the source in person.

With Dmitry previously not allowing anyone from outside

Russia to visit the mine and with his aversion to cameras,

the plethora of information on the internet has to date been

nothing more than guesswork.

Even in the host rock, the natural green

hues of the gem are breathtaking. I have

previously witnessed Emeralds and green

Garnets in the host, but nothing can

compare to the electrically vivid colours we

were looking at. Considering the lack of

light caused by the overcast sky, the Chrome

Diopside looked magical! Even the opaque

green conglomerate and areas of chromium

dust looked like a gift from Nature.

As the rock face we were evaluating was

no longer an active mining area, I asked

Dmitry if I could take my hammer and see

if I could find a few gem quality pieces. He

seemed to find the request amusing and

probably thought that if his experienced

team hadn’t found anything then I would

have no chance. However, without blowing

my own trumpet, after visiting hundreds of

different gem mines in dozens of different

countries, you develop a bit of a sixth sense

of where to look.

you develop a bit of a sixth sense

of where to look.

It was amazing, that with so much

chromium in the ground, how few pieces of

clean crystal we could find. The only time I

had ever witnessed anything like this was at

the Peridot mine in Changbai. There, the

hillside was coloured green by the presence

of billions of pieces of sand sized Peridot.

Here though, it was the trace element of

chromium and not iron that was the source

of the electrifying forest green colour.

Next, I went and sat by the tailing of the

season’s digging. I thought I might have

more success scouring through the waste

of the previous dig, than actually digging

myself. I had a little bit of a success in

finding some semi-gem quality crystals, but

these were so small they would be difficult

to facet (see photograph with hammer).

For a combination of reasons, this season’s

mining had finished a little early. Firstly,

bad weather had already been forecast

and the next part of the chromium vein

where Dmitry hoped he would uncover more

pockets of gem quality Chrome Diopside,

is currently underground. The gem-bearing

vein runs at 45 degrees and there needs to

be a lot of earth moved before he will know

if there are more gem-quality rocks to be

discovered. With the rainfall of the past

week, a small lake had formed at the very

place he will need to dig. Dmitry had installed

a pump to extract the water but as the rain

continued, his attempts were sadly futile.

Dmitry then showed me some gloriously

coloured large Chrome Diopside crystals

that they had extracted towards the end of

the season. After I had evaluated them I

told him that they would actually probably

end up being cut into several smaller

stones. I explained that for most gems, the

bigger the size, the more vivid the colour

saturation. If you think about the likes of

Csarite, Morganite, Kunzite, Tanzanite or

Aquamarine, it’s really difficult to retain

colour saturation in smaller sizes and

therefore the lapidarist will try and ensure

that the brilliance is maximised (it’s a good

principle to remember that the lighter

the tone, the brighter the brilliance that

can be achieved). However, with Chrome

Diopside it’s normally the opposite. As the

size increases, the stone becomes darker

and loses some of its vivid saturation. Any

faceted piece over one carat which retains

a vivid saturation and does not become too

dark in tone, is extremely rare! It is for this

reason that larger pieces often tend to be cut

into several smaller pieces to really allow the

gem to showcase its spectacular saturation.

Considering that just a few hours ago Dmitry

was so camera shy, he seemed to be really

enjoying seeing us filming and documenting

his deposit. He even asked if we could take a

few pictures of us with him in them. Seizing

the moment, I explained that in our flightcase

we had a drone (a small helicopter with

a built-in camera) and if we could have his

permission to get an aerial view over the

mine. By now he had realised the purpose

of our visit wasn’t just to buy gemstones, but

to share his unique story to gem collectors

around the world. He was now much more

forthcoming in supporting our efforts.

After a few hours, the light began to fade

and Dmitry suggested it was time to have

some food. While my cameraman, Alex

continued to eke out every last moment of

filming time, Dmitry set up a bench and

Eugene and I searched the area for firewood.

It turned out that Dmitry was quite a cook!

Some weeks before he had been out hunting

and had prepared us some amazing smoked

antelope. Whilst some of the other local

delicacies he had prepared were a little bit,

should I say 'unusual', the antelope was

phenomenal. And being in Russia, it was

important to adopt the local tradition of

washing down the meal with a few glasses of

local vodka.

One of my golden rules is never to discuss

gemstone prices either after a drink, or more

importantly, at the source. When you are at

the mine and you see all of the hard work

that goes into extracting the gem, and as

you begin to truly appreciate the severity of

its scarcity, you will always end up paying

more. But in all of the excitement of the day,

I broke both rules at the same time and we

started to openly discuss pricing.

We chatted about how in China, one of the

leading retailers of coloured gemstones –

Sino Jewels, recently launched a collection

called ‘Crispy Green’. This collection is just

one of many that can now be seen in retail

stores across China. The problem for us in

the West is that when China starts to adopt a

particular gem in bulk, the supply can dry up

very quickly. With demand outstripping the

speed of extraction and with every year that

goes by, the quantity of Chrome Diopside

coming out of the ground is diminishing. So

it’s not surprising that Dmitry wants a higher

price than we had previously experienced.

Whilst I had been drawn into the discussion

about pricing, I still had just about enough

sense not to commit to any pricing

agreement and suggested that I needed to

sleep on it. By this point I had been awake

for 31 hours straight. I was absolutely

exhausted! Despite the insalubrious sleeping

conditions, the wonderful vodka did its job.

With the cold night air, the satisfaction of

finally seeing the Chrome Diopside deposit

made me extremely warm on the inside and

I dropped off into a deep sleep.

The next morning I awoke early to the

sound of rain on the tin roof. Sadly our good

fortune had turned against us and it was not

possible to spend the day at the mine.

Eugene kindly accompanied us on the

drive back to Neryungri airport where

we spent most of the journey organising

a trip to his favourite place on the planet,

the Ural Mountains. He had spent many

a year working there at the Alexandrite,

Emerald, Topaz, Demantoid Garnet and

Siberian Amethyst deposits and he invited

me to take a trip there with him next year.

With our trip being cut a day short because

of the weather, we said our goodbyes

and decided to go off and try and find

the source of Charoite. Sadly, we weren’t

successful, so for the moment, that one

stays on my Bucket List.