There’s something very enchanting about the idea of finding treasure. With glittering gold, spectacular silver and glorious gemstones, a treasure chest full of goodies is firmly in the realm of fantasy for most people. But less than an hour away from our studios in the Midlands, a hoard of over £3.5 million in Anglo-Saxon gold and silver was found: the largest ever find of its kind.

With over 4000 objects crafted from 5kgs (11 lbs) of gold and nearly 1.5kgs (3.3 lbs) of silver, this remarkable discovery in the Staffordshire countryside was found by a metal-detectorist in 2009. Although the size of the find is in itself remarkable, the Staffordshire Hoard is prized so highly due to how much these gold and silver pieces can tell us about Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship, society, beliefs and trade at the time.

THE HOARD

Nobody knows exactly why the Hoard was hidden away where it was. It was buried in around 650-670AD and was originally crumpled up into a bag or a box. It was quickly stowed, rather than ceremoniously buried. It was hidden in what was a remote, wooded area, just off ancient Watling Street, one of the most important roads in the UK at the time (now known as the A5). Almost every item in the Hoard is military-wear, showing signs of having been ripped from enemy soldiers as the spoils of war then crushed into a container. It was likely plundered from the battlefield and hidden in a hurry. Presumably, the owner was expecting to return but wasn’t able to. An alternative theory is that it was either stolen from, or was being brought to, the King of Mercia (the Kingdom of Mercia encompassed what we call ‘The Midlands’ today). In the Anglo-Saxon period, the King of Mercia lived at nearby Tamworth Castle, making it one of the most important towns in the country and making Watling Street an extremely busy route. Mercia was expanding quickly at the time, gaining surrounding territory through war with neighbouring Kings. Battles were happening regularly in this area. Regardless of why it was concealed, the Hoard remained buried in the ground, untouched for over 1,300 years.

EXCEPTIONAL CRAFTSMANSHIP

Although the Staffordshire Hoard doesn’t contain jewellery, the same skilled craftsmen would have created these items. Since Mercia didn’t have its own resources for silver and jewels, we know that these raw ingredients would have been bought through trade. Gold was likely to have been melted and reused. Although the Hoard is mostly items of weaponry – parts of swords and helmets, by and large, they show much of the same elaborate techniques that were popular in jewellery at the time, like filigree, Garnet cloisonné and foil work. Many of these techniques are still used in jewellery-making today, using similar tools.

WHY IS IT SO IMPORTANT?

The fascinating thing about the Hoard is that it throws light on the intricate beauty and skill being used by craftsmen during this period. People often refer to the 'Dark Ages' after the fall of the Roman Empire and the perceived decline in society, art and philosophy, however the Staffordshire Hoard really underlined the fact that, far from being a time of ignorance and hardship, it was (for some at least), a period of enlightenment and wealth.

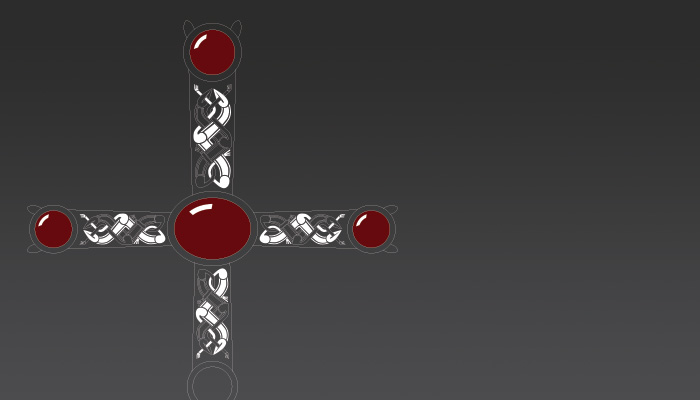

At this time, Britain was beginning to be converted from Paganism to Christianity. Mercia was one of the last kingdoms to officially take up this doctrine. The pieces in the Hoard mark this transition in a fascinating way – with a mixture of Christian symbols and Pagan iconography, it can be assumed that this conversion was a slow transition, rather than an abrupt change. In some pieces, both symbols can be found alongside each other, as part of the same design. One of the most impressive of these is what is called the ‘Folded Cross’ or ‘Great Cross’ (overleaf and recreated on this page), which is probably the most well-known artefact in the collection. This cross was intentionally dismantled, with its largest Garnet gemstones removed, and folded up to fit inside a bag or box. It was probably part of the front cover of a Bible, but despite this obviously Christian use, the arms of the cross were decorated with panels of interlaced animals, following the Germanic Pagan tradition.

Another intriguing artefact is a gold strip, bent in two, inscribed with the following Bible verse, “Rise up, LORD, and let thine enemies be scattered; and let them that hate thee flee before thee." This vengeful Old Testament God would have been easier to integrate with the Pagan Gods previously worshipped here. Researchers have used this information to look into how the conversion of the native population was achieved. In the early days at least, it seems that Christianity was added into the overall religious narrative practiced here at the time, creating a slow transition, rather than being a very new and separate idea.

CLOISONNÉ

The Staffordshire Hoard is best known for its Garnet Cloisonné work. This technique had been very popular since the later years of the Roman Empire and had subsequently spread across Europe. This extremely intricate style involves thin strips of gold being attached to a gold base to create 'cloisons' ('partitions' in French). These were then partly filled with a sticky paste, sometimes made from beeswax. An extremely thin layer of gold foil (around the same thickness as modern tinfoil), stamped with a die to create a ‘waffle’ pattern, is then laid into each cell. Next, a thin slice of Garnet (around 1mm thick) is placed onto the foil backing. These were presumably made with a cutting wheel, then shaped by hand into the precise shapes needed. Some pieces were shaped to curve round an edge on the final piece, requiring exceptional skill. Finally, the metalworker would have rubbed over the surface. Since gold is so soft, this would have flattened the tops of the cloisons, locking the Garnets in place.

The thin slices of Garnet wouldn’t have reflected very much light, so the gold foil backing was used to reflect light in a similar way to a modern bicycle reflector. The Garnets they used have been analysed and are thought to either come from the Czech Republic, or from India, where we source the majority of Garnets we sell here at Gemporia today.

One of the most interesting pieces in the Hoard was a gold pommel cap with cloisonné decoration. There are many of these caps, which would have covered the handle end of a sword, but this particular one draws the attention as a few pieces of Garnet have been replaced. The originals probably fell out and the owner couldn’t replace them and so he used coloured glass. At the time, the glass would have blended seamlessly with the Garnets, however, over time, the glass has discoloured, while the Garnets have kept their colour perfectly. In fact, there are a few pieces of glass to be found in the Hoard and almost all of them have discoloured or disintegrated. The Garnets and precious metals have fared much better.

FILIGREE

Some of the most mesmerising pieces in the Hoard have intricate filigree detailing. This method is still used today, including in our design houses in Jaipur. Metal wires are soldered to a base plate in ornate patterns. These short wires were either twisted or beaded to create different effects and were usually made up of two thin wires (around a third of a millimetre thick), on either side of a thicker one (around three-quarters of a millimetre thick). Sometimes it is possible to see scratch marks on the base plate which were used as guides by metalsmiths, showing them where to solder the filigree work.

One of the most impressive pieces in the Hoard with filigree detailing is the Double-Headed Mount. With exquisite S-scroll filigree, this impressive piece is likely to represent a horse or a seahorse. Although only one head remains, it would have had two mirror-image heads in its original form. This is an example of 'split representation'. This was a way artists would challenge the viewer to imagine a flat design in three dimensions.

ANIMAL INTERLACING

One of the most intriguing patterns to be found in the Hoard is Animal Interlacing. Made using stamping, filigree or carving, these patterns originally came from Germanic influences, but were later incorporated into what became known as ‘Insular Style’ – a blend of Germanic and Celtic traditions. Birds, boars, fish, horses and serpents were commonly seen and each had their own symbolic associations. They also created 'zoomorphs', patterns that are animal-like, often creating deliberate conundrums or visual riddles.

One of the most captivating artifacts with animal interlacing is the Helmet Cheek-Piece, shown at the very top of this page. Writhing serpents and quadrupeds twist through one another. Some of the four-legged animals reach back through the serpents and bite their own S-shaped bodies, a little like the ancient ‘Ouroboros’ circular snake symbol, representing eternity. Not only is the complexity of these weird and twisting animal shapes astonishing, but the craftsmanship required to create them is astounding as well.

STAMPING

Stamping was a way to decorate bowls, drinking vessels, scabbards and helmets. A thin foil (usually of silver) around half a millimetre thick was placed on a die. A piece of softer lead was placed on top, which was then hammered, forcing the silver underneath into the die and imprinting the design. The foil pieces were held in place by rivets and pins to add a 3D pattern to a piece of work. Hundreds of fragments of foils were found in the Staffordshire Hoard, including this intriguing line of moustachioed heads.

There is something humbling about seeing a collection like this. Gold, silver and Garnets shine brightly, hardly betraying the centuries that have passed since they were buried. Their worth can be measured not only in their monetary value, but also in the insights into craftsmanship and artisanry these items hold. As glass becomes dull, as saplings grow and mighty oaks fall, as timber rots away and as kingdoms come and kings go, some things last. Seeing these wonderfully preserved treasures sparking is an astonishing reminder that Mother Nature creates a few rare treasures that will outlast us all.

For more information or to arrange a visit, see www.staffordshirehoard.org.uk.

Photos: Birmingham Museums Trust