On 27th September 2019, our head of gemstone buying, Jake Thompson, received a phone call from a good friend of ours called Roshan, whose family have been our main supplier for Spinel from Burma over recent years. To say he was overexcited would be an understatement. He told Jake that he had to come to Burma immediately.

Words by: David Troth

Jake’s immediate reaction was that foreigners couldn’t travel in the Mogok region of Burma. “No,” said Roshan, “the government have lifted the travel ban on foreigners, and I’m sure I can get you a permit to travel through the region. I can even get you a temporary filming permit.” Jake could not believe what he was hearing. Mogok has been closed to all foreign visitors for many years. Roshan insisted that “Mr Steve and Mr Dave must come too, as it will be one of the most historic and important journeys Gemporia have made to-date”.

Roshan is the fifth generation of his family to live in Mogok, the northern-central city of Burma that is famous for its quality gemstone mines. Roshan’s ancestors were from Nepal. Just like Gemporia, they are a family business, and they have 60 years of experience mining Spinel and Ruby. Roshan’s father was so prominent in the industry that he became the government minister for mining. Roshan has five brothers and six sisters, all of whom are involved in gems. But that’s not unusual in Mogok. Of its 200,000 inhabitants, 60% of adults are said to work in the gem trade. Our founder, Steve Bennett, was already in the Far East when Roshan’s call came, and within just a few days our visas, flights and Mogok travel permits were all sorted. It took three long flights to get there, but in record time myself, Jake and Steve were landing in Mandalay, the second-largest city in Burma.

Even under British rule, Mogok, with its rich treasure trove of gemstones, was kept as a separate independent state. In 1942, while Japan was invading Burma, many locals took refuge by digging holes in their gardens and hiding underground. It is said that many of them found precious stones during this time, and while enduring the invasion, were busy mining for the future wealth of their families. Three years later, Britain regained control, and in 1948 Burma was granted its independence.

Mogok is home to the finest Sapphires and Rubies in the world and is 4,000 feet above sea level. The Mogok Valley itself is 20 miles long and two miles wide. Gem deposits seem to be focused within a nine-mile radius of Mogok. Both the Rubies and Spinels were formed in a white dolomite matrix of granular limestone. The host rock was altered by contact with molten igneous material which recrystallised the calcium as calcite, and the impurities created the beautiful gems we now enjoy. Today, lucrative host rock mining has finished, and miners instead search through the alluvial gravel. In the 1950s, the total mining yield in Mogok was about 70,000 carats of Ruby and Sapphire, but only one in 20 pieces was ever described as being of decent quality, and only one in 200 as gem quality.

We met Roshan at the airport, where he told us that he was delaying our trip to Mogok for a day or two. To say we were disappointed would be putting it lightly. “No, no,” he replied, “it’s great news. I have hooked up with a few of my friends who mine Jade in Mogaung, they are in town for the Jade market, and they have managed to get you a pass. This never happens, it is normally only the Chinese buyers allowed in. The miners want to meet you today, and I also want to show you where we cut Jade.” This confused us all, as we thought all the Jade trading was done in China. “No no, that’s the secondary trading, the first trading is done here in Mandalay. I want to introduce you right to the source.”

The northern mountainous region of Kachin is the source of Burmese Jade. Its highest mountain, Hkakabo Razi, rises almost 6,000 metres above sea level, forming the southern tip of the Himalayas. The region is home to the world’s only source of gem-quality Jadeite (the most prestigious grade in Jade, not be confused with Nephrite Jade). It is mined in alluvial deposits of the Uyu River in the township of Hpakant. The region is right on the Chinese border, a country that has virtually worshipped the gem for centuries. Visiting the Jade mines was an offer we couldn’t turn down. Myself, Jake, and our cameraman Connor travelled with Roshan to look for Sapphires, while Steve briefly detoured to the Jade mines. The smaller-scale mines he observed are where some of the finest grades of Jadeite are unearthed. With Steve being so desperate to get back to see the Spinel mine, his time here was short, but we wanted Steve to go and build relationships with the mine. And that’s precisely what he did – we now have an excellent source of Jadeite.

Mogok has a very different feel to the other places we visited in Burma, which is also known by the more modern name of Myanmar. It still feels like a separate state. The permits we needed also apply to the non-Mogok residents of Burma! Roshan told us that the queues to get in would often stretch for miles, as Burmese residents would be hoping to gain access to what they call ‘Rubyland’.

Mogok has been in existence for 800 years, ever since hunters of the Sab Bwa of Momelk lost their way in the thick jungles in the heart of Burma and took shelter under a tree for the night. At daybreak, they heard birds singing and hovering over them. Investigating the commotion, they ran into a clearing full of beautiful Rubies. They collected as many as they could carry and brought them back to their leader. He immediately realised their wealth and thus, Mogok was founded. Ever since, the Mogok area has been very secretive, hiding its treasure not just away from the rest of the world but indeed the rest of Burma. Most trading took place in the city of Mandalay, about a ten-hour drive south.

The first mine we visited was one of the most well-respected Spinel mines in the area, which has been run by the same family for many decades. The mining here was done alluvially by digging up soil and occasionally by breaking down huge boulders. The earth and smaller rocks were then panned in the stream, and the remaining stones were flipped over onto the bank. As Spinel’s density causes it to sink to the bottom, flipping it over brings the gems to the top of the pile after flipping. Here, we saw the team picking both Ruby and Spinel crystals out of the spoil, and putting them into small bottles. After a week of mining like this, these bottles still wouldn’t be anywhere near full. Seeing this process gave us great insight into why Spinel’s value is again rising. We see the demand for Spinel at the Tucson and Hong Kong gemstone fairs, but being among the very few foreigners to ever visit this source has helped us understand how scarce these jewels are becoming. The stones we watched them collecting were not even approaching quarter carat sizes.

The Mogok residents and miners that we met were excited to learn that we were British, as they believe the British Crown Jewels have played an enormous part in the demand and subsequent price increase of fine, facet grade Spinel from Mogok. They all tell the same story about the finest Ruby ever mined here, and although records do not exist detailing the specific size, it is accepted locally that this was indeed the Black Prince’s Ruby. This is the stone that sits front and centre in the Imperial State Crown, which was later tested and confirmed to be a Spinel.

The second mine we visited was Roshan’s. We’ve been working with him and his family for years to bring their Spinels to market. For generations, this same family has been mining Little Gem Mountain, as it is known locally. This mountain emerges from the dense jungle and watches over us like a guardian of the stones. Roshan told us of a time in the 1970s when there was a problem with the lease of the mining rights. So valuable was the mine to the local community that the villagers filled in the entrance, because they all share in the spoils of the mine and they didn’t want anyone else to find the treasure hidden below!

Today, they mine hundreds of metres into the mountain. The shafts wind and meander into the natural cavities that harbour gem rich seams. They tell stories of how they find a gemstone vein which will be productive for a time before it dries up. It may be a decade or so before they find the vein elsewhere in the mountain. Geologically, mining here isn’t like the host rock mining of Tanzanite. Here, the alluvial deposits of Ruby and Spinel have coursed through the mountain like the veins in our bodies. This is why the locals keep digging towards the heart of the mountain, believing it to harbour a treasure that Mogok has not yet revealed. The gem bearing soil, also called ‘pay dirt’, excavated from inside the mountain makes its way down the hillside in a series of stages where the miners work hand in hand with the landscape. Mother Nature provides streams in which to wash and sort the stones. The spoil is panned and sieved several times, with each sieve having smaller holes than the one before. By the end of the process, even the very smallest stones are saved as there is value in every stone. The nearby village is home to a series of artists who paint with Mogok’s natural treasures, and they require the finest and smallest stones to give nuance to their vision.

All the mining that we witnessed was being done using the same artisanal methods as were used hundreds of years ago. Gone are the mechanised methods used for three-and-a-half decades. Sadly, their relics are still on view in the valley, blotting the landscape with vast, rusted sorting chambers, cascading down the mountain like an industrialised waterfall. With decreasing yields, artisanal local family miners have been able to return in the stead of the corporations, working as they had for 800 years in harmony with nature. Now, they’re moving the soil not with huge diggers, but with picks and buckets, then sieving the ‘byon’ (the local word for mixed gravel) with just their bare hands and dinner tray sized sieves.

On the way to visit the third mine, Roshan wanted to show us something. He had the team drive to the top of a hill, and he pointed at a building on the shore of a vast lake in the middle of a valley. He said, “That is Mogok gem market. We used to have to drive to Mandalay, which is many many hours by car, but now we are open for business.” He explained that now Mogok is open to a select number of trusted foreigners, the miners hoped to conclude all their business here, rather than further south. He had cleared it for us to enter the gem market of Mogok and see the stones on offer.

He shared with us that in the late 1800s, the British used scientific mining to ascertain where the Rubies were located, and it turned out they were mostly under the homes of the Burmese people in the centre of the town. The British agreed to buy all of the houses off of the Burmese people, compensating them healthily as well as clearing thick jungle to build them new homes and promising them employment in the new Ruby mines. In this period, millions of dollars of Rubies and Sapphires were mined.

The British then brought electricity to the area and provided it to every home. In 1896 the British backed mining company agreed to pay the government a tax of about $800,000, plus one-fifth of any profits for 14 years. This contract included all of the mines within a ten-mile radius of Mogok. Many locals still remember this time as a golden era, because everyone was working and there was a lot of money in circulation.

The old British mine was the most prestigious of its day, a memory of the brief British presence in Mogok. It once produced a fine 42-carat pigeon blood red Ruby in 1906. After cutting, the Ruby weighed 22-carats, and an Indian gem dealer later acquired it for a significant sum. Because the extensive excavation of the mines was walled by a valley, decades of heavy rainfall in this area has filled the old abandoned mine, and it now sits at the bottom of the beautiful lake right beside the gem market. The locals still talk of the undiscovered Rubies and Spinels that might lie in her depths, and Roshan’s brother Bishnu is one of the few that will admit to diving for treasure at nightfall.

The next mine we visited was known as Ruby Creek, and we were told that some of the largest and most beautiful pigeon blood red Mogok Rubies had been pulled from an ancient river bed here. The miners here took great joy in showing us the day’s finds, which were beautiful, river worn gems of both pink and red. We couldn’t be sure if they were Ruby or Spinel on first glance, but either way, they were very fine.

After a few more hours in our convoy snaking through the jungles of Mogok in monsoon season, we arrived atop a steep track that led down into a bustling and colourful Corundum (Ruby and Sapphire) crater that lay hidden behind a jungle curtain. As we made our way down the track, we saw tent after tent laid out around the basin like a gemstone amphitheatre. In the middle of a vast clearing was where water drained after washing through the ‘byon’ as the prospectors here continued their search for gems. This mine was one of my favourites; the atmosphere was one of anticipation and jovial camaraderie. The miners all knew each other well, and each shaft in the ground operated like an independent cooperative. Many of the shafts were family ventures.

We met a band of brothers who had been working together for years. Sanny, the joker of the pack, called us over and introduced us to the mine owner, Zia. They all explained to us that they work like a cooperative and share the profits. They couldn’t stop smiling because recently they had found two Sapphires that had sold for a total of over $60,000. Hearing stories like this reminded me why everyone in Mogok is so invested in the gem trade. This is the land where dreams come true, and every family we met had their own fairy tale to share.

Roshan invited us for lunch at his family home, and upon arriving, we were frozen with fear at the deep intimidating bark of a 180lb rottweiler! After Roshan reassured Baloo that we were family, he turned out to be a real sweetheart, and we later found out what he was guarding. Over a table full of delightful Nepalese home-cooked foods, Roshan explained that Mogok was a thriving melting pot of many different nationalities who made their way to the area in search of gemstones generations ago. It was here, after lunch, that we were invited upstairs to the office of his older brother Bishnu, where they explained to us how the intricacies of Mogok work. Each house specialises in something, whether that be Sapphire, Ruby or Spinel, or even different grades of those stones and in the preforming and calibration of them.

We viewed some incredible parcels of Spinel, including the famed fluorescent Jedi Spinels, named as such because their brightness knows no dark side! We also saw some blue-grey Spinels that are now commanding a considerable premium in the market. This news has filtered back to Mogok, and they are now being re-sorted from mixed colour parcels into their own parcels, driving their price up even more! A parcel of mixed Spinel was also laid on the table, which is usually a great way to get a deal. Because the stones haven’t yet been sorted into the colours that may command a premium, we typically end up paying a reasonable average across all colours. Not any more! It seems that all these rare colours are commanding huge premiums as long as they are clean and bright. Designers are craving mixed natural colours, and Bishnu explained that premiums are being paid even for the mixed parcels.

After much deliberation, we agreed on some special deals and then, to celebrate, we went to enjoy some traditional herbal tea on the balcony. From here, we took in the sight of lush, jungle-covered mountains draped sparingly with a blanket of clouds. As breathtaking as this was, we wouldn’t help but mention the elephant in the room, because at our feet was a considerable parcel of gem grade rough Peridot, laid out on a blanket in the rain. This is what Baloo the rottweiler was guarding!

Roshan and Bishnu explained that in the whole of China there is only one mine that offers the finest Peridot, easily as fine as Kashmir Peridot and finer than the stones found on the Red Sea island of Zabargad. Due to the demand for this incredible grade of Peridot, Chinese buyers come to Burma to source it, take it back to China and call it their own. This explains the sharp global increase in natural Peridot prices that we have seen in the last two years. The Chinese buyers are paying $200 per carat for the Burmese gems, and this is why the Peridot at Tucson and Hong Kong is north of this figure. We don’t foresee it coming back down any time soon. The Burmese Peridot was the finest any of us have ever seen, and we bought a small parcel for the Gemporia museum in our building.

This incredible journey of discovery was a real eye-opener to all of us, and we can’t wait to present to you the wonderful stones we were fortunate enough to source. We learned so much from Roshan and his wonderful family, and cannot thank him enough for the phone call and subsequent efforts that allowed me, Steve and Jake to travel an area we thought we’d never see with our own eyes. This short trip may have been over in a flash, but the jewels, the people and the stories of Burma will stay with me forever.

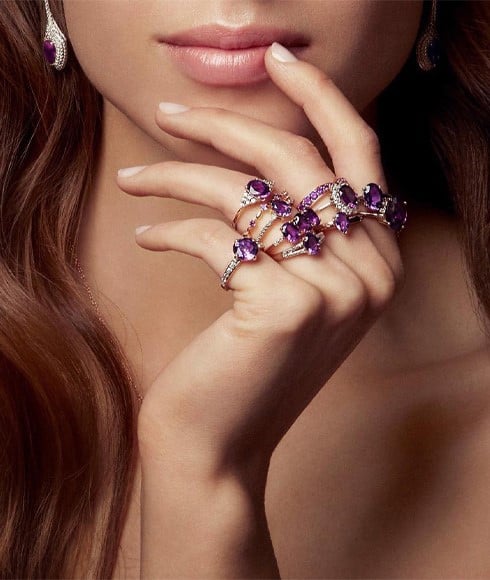

EXPLORE OUR BURMESE SPINEL DESIGNS

EXPLORE OUR BURMESE RUBY DESIGNS